Lesbian Mothers, Mass Murder, and "Wide-Open National Sin"

The Rise and Fall of Jerry Falwell's "Moral Majority"

On September 13th, 2001, just following the 9/11 attacks, Reverend Jerry Falwell Sr. somewhat famously reproached the American people on fellow televangelist, Pat Robertson’s talk show, The 700 Club:

And, I know that I'll hear from them for this. But, throwing God out successfully with the help of the federal court system, throwing God out of the public square, out of the schools. The abortionists have got to bear some burden for this because God will not be mocked. And when we destroy 40 million little innocent babies, we make God mad. I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People for the American Way — all of them who have tried to secularize America — I point the finger in their face and say "you helped this happen."

Falwell revised this stance the following day, remarking, “I would never blame any human being except the terrorists, and if I left that impression with gays or lesbians or anyone else, I apologize.” Yet just prior his death in 2007, in an interview with Christiane Amanpour, he reasserted his position: "If we decide to change all the rules on which this Judeo-Christian nation was built we cannot expect the Lord to put his shield of protection around us as he has in the past."

The appeal to a “Judeo-Christian nation” remains a powerful American origin story among many conservative Christians, particularly evangelicals. It refracts a fantasy of a nebulous past wherein all Americans believed in a Christian God, and that somehow our institutions mirrored this belief. This story has long shaped the Christian right’s worldview, making way for numerous successful moral panics, built predominantly from a fear that we have moved away from our godly origin and into an epoch of fornicating homosexual abortionists. It’s is a useful, regulatory narrative, capacious enough to reenforce a set of seemingly timeless, divinely articulated “rules” (to borrow from Falwell himself) without actually having to interrogate them.

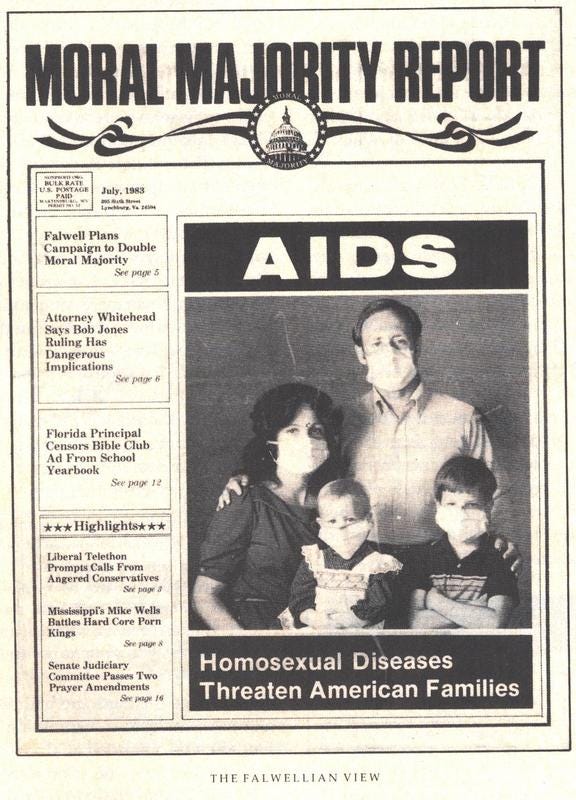

In this context, Falwell’s beliefs are, in fact, fairly unexceptional, although they feel alarming and extraordinary from the outside. His track recored for open bigotry is prolific. He made equally foul claims regarding integration, notably in a 1977 sermon entitled, “Segregation or Integration: Which?” he insisted that, “the true [Black man] does not want integration...He realizes his potential is far better among his own race...It will destroy our race eventually.” Further reaffirming segregation’s biblical, and thereby unquestionable, origins, he concluded, “It boils down to whether we are going to take God's Word as final.” In 1993, amidst of the AIDS epidemic, Falwell admonished that, “AIDS is the wrath of a just God against homosexuals.…It is God's punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals.”

I write about Falwell not simply because he and his Liberty University legacy are easy targets (please recall his son, Jerry Falwell Jr.’s 2020 sex scandal), but to highlight his leadership in the creation of the “Moral Majority” in the late-1970s—a political organization that sought to unite the religious right and the Republican party. It was built on a foundational belief that there is a silent majority of Americans who share this “moral” vision, and that in unifying, they could gain real political power.

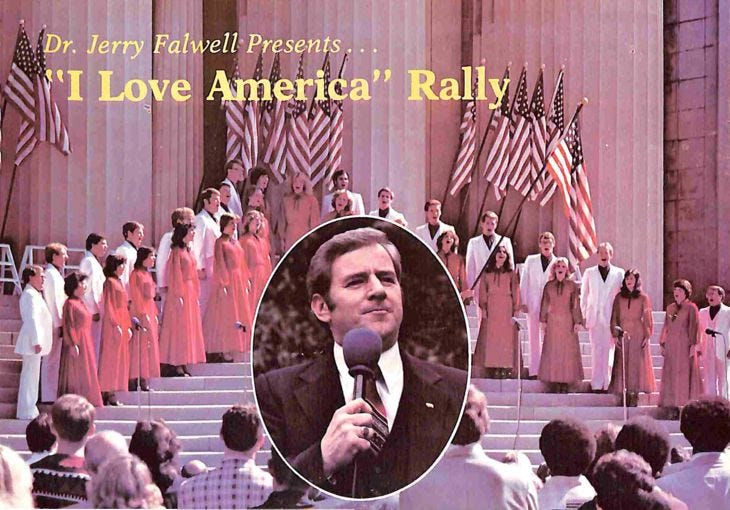

The group originated in 1976, when Falwell began his “I Love America” campaign, in which he held rallies across the U.S. focusing on the social issues he felt to be important. Significantly, he broke away from a conventional Baptist position that upheld a separation of church and state in favor of their “reunification,” citing his fear of “growing moral decay.” In his newsletter for “The Gospel Hour,” Clean Up America Hotline Report, he describes the origins of his “I Love America Club,” he laments the country’s embrace of “wide-open national sin,” beginning with the "outlawing” of the Bible and prayer in public schools, to the “three to six million unborn babies that have been aborted” since January 1973. “According to the Bible,” he adds, “this is mass murder.”1 He continues his litany of alarm by discussing sex on tv, porno magazines, a growing acceptance of homosexuals, the Equal Rights Act, socialism, communism, and my personal favorite, “a major American city daily newspaper” in which he read about “two lesbians who were planning to marry and adopt children.”

Given the success of “I Love America,” in June 1979, along with Paul Weyrich (co-founder of the Heritage Foundation), Falwell officially founded the Moral Majority. Their goals were fairly simple: to drum up a narrative of social decay by emphasizing moral urgency around particular social issues. This included calling for the prohibition of all abortions, opposition to homosexuality, pornography, and divorce, as well as the promotion of “family values,” prayer in public school, proselytizing to non-Christians, anti-communism—among others. These pressing political questions became the fodder that enabled the group to garner wider conservative Christian interest in their own mobilization, “taking back” the country they imagined to be wrested from them.

Importantly, this movement was a way to show evangelicals that they could unite with other religious conservatives—including Catholic, Mormon, and Jewish groups—who shared their political vision, without “sacrificing theological principles.” Their lobbying helped to propel religious conservatives visibly into the political sphere, successfully garnering significant political power through their convergence with the Republican party.

Falwell’s Moral Majority played a key role in assembling a structured language of authority in response to multiple liberation movements happening in the 70s and 80s—women’s rights, gay rights, abortion rights, and civil rights. White evangelical political opposition to these movements was not organic but produced— and perhaps even coerced— through strategic, fear-driven narratives of social collapse, justified by those who claimed divine authority. I say this not to absolve evangelicals from their complicity and participation in harmful practices, but to emphasize that belief is not inevitable (or even biblical in this case). This kind of fundamentalism is a collection of origin stories, designed to uphold the very logics that have sustained neocolonial and white supremacist systems. Used strategically, they capture the fears and allegiances of the many, while making a few really, really rich.

Out of curiosity, I reached out to my parents to find out what they remember about Falwell’s campaigns, and how it touched their own 1970s Baptist communities (they would have been teenagers). Neither recalled much other than the fact that he was “a bit extreme.” Notably, my mom asked, “[didn’t] Jerry allegedly [think] that Tinky Winky the Teletubby was a homosexual?”2 So in terms of my own immediate familial connections to a Falwellian flavor of evangelicalism—I can claim very little.

Falwell dissolved the Moral Majority in 1989, extolling that “our mission is accomplished…. the religious right is solidly in place,” audaciously adding, “like the galvanizing of the black church as a political force a generation ago, the religious conservatives in America are now in for the duration.”

It’s hard to take seriously such an egregious and charismatic religious figure like Falwell—his teachings and legacy have, time and again, proven to be overwhelmingly harmful. His 2007 death was eulogized by friends and critics alike. In Christianity Today, Christian author Stan Guthrie called him, “a recovering fundamentalist” who “made evangelical political involvement the norm, no matter how many toes he stepped on both inside and outside the camp.” Notable evangelical atheist, the late Christopher Hitchens, bemoaned: “It’s a shame that there is no hell for Falwell to go to, and it’s extraordinary that not even such a scandalous career is enough to shake our dumb addiction to the ‘faith-based.’”

Abortion enters into this story indirectly— as part of the tapestry of moral panics Falwell contributed to throughout his life. As I wrote previously, opposition to abortion rights were not always part of an evangelical agenda. Yet the timeliness of Roe v. Wade, in tandem with feminist and civil rights movements, brought it to the forefront, strategically politicizing a significant U.S. demographic through an appeal to “life,” urging the American public to “think of the children”—unborn, imagined, and (sometimes) born.

Famously, the Bible doesn’t mention abortion. There is, however, one specific Hebrew law in Exodus that stipulates a punishment for injuring a pregnant woman to the point of miscarriage. This is where the idea of fetal personhood seems to originate.

To Falwell’s credit, Tinky Winky was absolutely fruity.